Intro

Predictive maintenance attracts a lot of attention these days. The kind that sets expectations high before anyone looks at a single data point. I’ve seen projects start with enthusiasm and still fall flat because the foundation was loose. The model was hardly ever the problem. It was how little care went into understanding the data that feeds it.

My work has taught me that success depends on how well we capture, clean, align, and interpret the signals coming from the machines (and their operators). The model only reflects what we give it. When the data carries the real behavior of the system, the predictions make sense. When the data is messy or misunderstood, the output becomes noise.

This article focuses on that quiet layer of work. The part that rarely appears in presentations, but decides whether a predictive maintenance project turns into a useful tool that people trust.

Predictive maintenance challenges

Here I describe how challenges show up at every stage of building a predictive maintenance model and how each stage influences the next.

1. Problem definition & business case

Predictive maintenance challenges often start before any data scientist trains the first model. They begin in meeting rooms where a project is approved because the idea sounds promising, not because its financial return has been understood. I’ve seen this more times than I’d like to admit. A model gets developed from a top-level directive, and the people who are meant to use it on the ground treat it as an outside mandate rather than a tool designed for them. That tension is hard to repair once it forms.

The deeper issue sits in the business case. Many predictive maintenance projects launch without a clear and realistic view of return on investment. I don’t mean a slide with optimistic arrows pointing upward. I mean a hard number that lives in the budget. When I work with production environments, and we want to reduce scrap, I can translate that goal into cost. There is the cost of defective output, the cost of the project, and the expected savings. Those numbers may not be perfect, but they are real enough to make decisions.

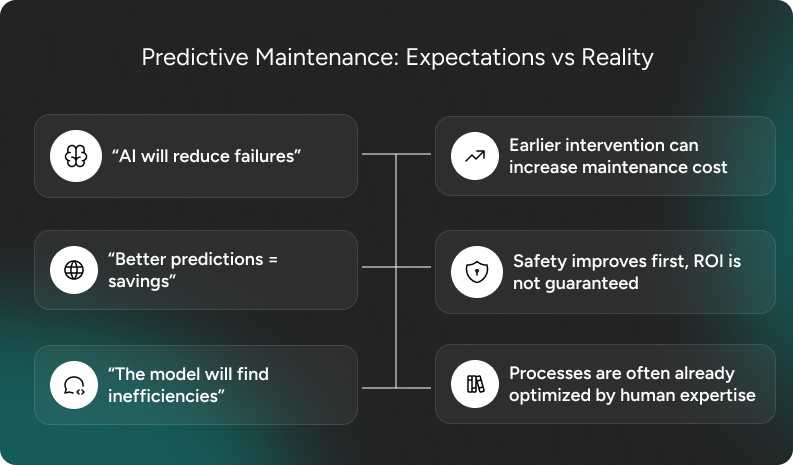

Maintenance adds a layer of uncertainty. Imagine a component that gets replaced every fixed number of operating hours. A model might spot degradation sooner than the scheduled maintenance plan. That sounds like an improvement. The catch is that earlier intervention may increase the frequency of repairs and raise maintenance expenses.

There is a trade-off between safety and cost, and safety comes first. Yet this doesn’t mean that the financial effect can be waved away. I’ve seen cases where the model worked better than the long-established procedure, but the outcome was higher expense with no measurable benefit beyond peace of mind. Not every improvement on paper is worth it in practice.

When expectations and reality don’t align

Another recurring challenge is the gap between what a client hopes to achieve and what is technically achievable. I’m currently involved in a project where the goals shift every week because the client hasn’t settled on what success looks like. They want:

- higher production throughput

- lower operating costs

- defect rates to stay where they are.

But those expectations fight each other. The production process has already been refined by people with decades of hands-on experience. Their intuition is not magic but lived expertise. The model cannot simply conjure gains where none remain.

Predictive maintenance projects fail when the desired outcome is not grounded in how the system actually behaves. And that misalignment does not come from malice, it comes from hope. But hope is not a business case.

Before building the model, I ask one simple question. What will we count as success, and how will we measure it in currency? If the answer is vague, the project is not ready.

2. Data collection & infrastructure setup

For some, data collection might seem simple. Clients often know what they want to track and already have some sensors running.

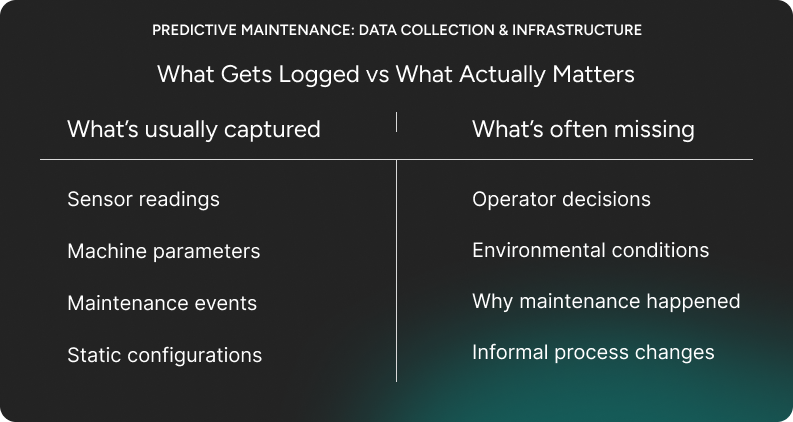

On the one hand, that’s true – many companies consistently collect parameters, and those readings are a good starting point. But on the other hand, sometimes valuable information goes unnoticed because it might seem irrelevant to the company.

For example, in manufacturing ambient factors like temperature or humidity inside the plant might be ignored, but they can directly affect equipment behavior. Also, I’ve seen cases where information was lost somewhere “between the lines”. For example, machines were inspected early not because they broke down, but because another unit was about to go into maintenance in the next 30-60 days. That kind of dependency doesn’t show up in the data – you only discover it once you talk to the people on the floor.

The same goes for aviation. I’ve heard of an airline, which couldn’t explain recurring engine failures even though all parameters looked fine. It turned out pilots had started taking off at reduced power to extend engine life. Nobody logged that change, yet it completely altered the wear pattern.

So the challenge isn’t only about “what” data you collect, but also “how” you decide what to trust and where it comes from.

Verifying data sources and sensor accuracy

At this stage, teams also need to analyze their sources, and ask themselves questions like: do we already have the right sensors, or do we need new ones? Are the existing sensors still accurate, or are they drifting over time?

Sometimes the sensor works perfectly, but the environment changes, so the data looks different. Understanding whether the variation comes from the machine or the conditions around it is critical.

The right storage and tools for the job

Then comes the question of infrastructure. Should you store data on-premises or in the cloud? Should it flow through IoT or SCADA systems? These aren’t purely technical choices because of governance, compliance, and security requirements.

Also, I’d like to warn you about what’s the most common data engineering mistake I’ve seen in these early stages of predictive maintenance projects. It’s picking the wrong database type. Many teams default to tools they already have or feel comfortable with, instead of choosing the right tool for the workload.

When dealing with large volumes of IoT data, time-series databases such as Azure Data Explorer or the TimescaleDB plugin for PostgreSQL can handle continuous streams of sensor data far more efficiently than traditional relational databases. They’re purpose-built for this kind of workload, and the difference becomes clear when your data volume grows.

3. Data exploration & preparation

Once we move into the data, the romantic image of machine intelligence meets the real world. This is the part of the project most people underestimate and it’s where I spend most of my time.

There’s a popular saying that data preparation is the bulk of any data science project. I agree, but in predictive maintenance the stakes are even higher because every data point might represent a physical process that behaves in subtle, messy ways. Cleaning and filtering alone are not mechanical tasks – they demand context. You can’t declare a spike in temperature to be an error if that spike is the first whisper that something is about to go wrong.

Sometimes an anomaly isn’t a mistake

I once worked on a production line that had six measurement points placed across a machine. Nothing exotic. Standard sensors. During normal operation, everything looked stable except for a small but persistent drift in a single location. At first glance, it looked like a faulty sensor, easy to discard. Yet, when we traced the behavior through the entire production sequence with someone who actually worked with the machine every day, we realized it was a signal of uneven load building up in the system. That small difference became one of the most meaningful features in the final model. It warned us before the full temperature spike hit and led to a sudden failure.

That moment shaped the way I approach data. I learned to slow down and ask whether something is noise or the system trying to tell us a story.

The trouble with false alarms

Then comes the other side. Sometimes the sensor is the problem. In heavy environments where equipment runs hot, vibrates, and lives through years of wear, sensors fail. A predictive model that relies on small deviations can end up firing alerts just because the measurement hardware has aged poorly. When that happens, trust erodes. The model might be right in theory, yet useless in practice because the data feeding it can’t hold up.

To avoid that, I walk the entire chain of data with the people who understand the equipment. Not just the files, the equipment itself, the process, the room it lives in, and the human routines around it. Without that, it’s easy to build a predictor that looks accurate on paper but acts like a nervous alarm system in the real world.

The hidden labor of understanding the system

The glamorous part of predictive maintenance happens later, during model training and validation. The hard part happens here, when I ask what a sensor means in context, how a failure manifests physically, and which odd behaviors deserve attention. This requires patience and listening. And it needs admitting that without hands-on knowledge from someone who has seen these machines break, the data is just numbers.

This is where predictive maintenance projects are won or lost. Not in the algorithm but in the understanding.

4. Model development & validation

In my experience, this is where most of the creative engineering happens. Every predictive maintenance project is different, so there’s no single algorithm that works for all. I always start by asking a simple question: what exactly are we trying to predict? Are we classifying, like deciding if a failure will occur, or estimating when it might happen? Or maybe we’re trying to group data to discover new patterns we didn’t expect?

I always start simple. For example, going with linear regression, decision trees, and logistic makes it easy to interpret and help you understand what’s really driving the results. You should move on to more complex methods later, only if you know that they’d actually add value.

Anomaly detection sits somewhere in between. When we already know what past anomalies looked like, we can train supervised models. But often, we don’t, and we only know what “normal” looks like. In those cases, the model needs to learn the baseline behavior and call out anything that doesn’t fit. That balance between known and unknown is what makes predictive maintenance extra challenging.

Time-based data adds another layer. Some signals can be stable, while others might fluctuate in unpredictable ways.

And one lesson I’ve learned is to not extrapolate beyond what the data covers. Every machine has an operating range, a “map” it follows. Once you go beyond that, predictions stop making sense. That’s why I often prefer tree-based models – they stay grounded in what’s real.

Model validation in practice

When we’re working across hundreds of similar machines, general models that spot shared patterns can perform well. But when every machine behaves a bit differently (and most do) it’s better to work with simpler, more targeted models. They’re faster to build, easier to understand, and more resilient when the data shifts.

Also, speed is another factor. In some projects, models only need to run every few hours, so heavier algorithms are fine. But if decisions need to happen in real time – say, during production – that’s a different story. The model has to react instantly, not in fifteen minutes, because in that particular case, fifteen minutes might mean disaster.

Designing for imperfection

No model operates in perfect conditions, because parameters change, data points might drop out and your sensors might become less accurate.

That’s what I call designing for imperfection. If one feature disappears or starts producing noise, the model should know how not to fall apart – for example, it should know that the Plan B is to switch to medians, fallback rules, or other safeguards we’ve built in.

Thresholds for failure detection or remaining useful life (RUL) need the same practical touch. They have to make sense to the people maintaining the machines. The best results come when technical precision meets real-world intuition, and when you know when to stop making things more complicated than they need to be.

5. Deployment & integration

Once the model performs well in testing, it’s time to bring it to life in the actual production environment. That means connecting it to live data streams, setting up dashboards and alerts, and making sure it fits into the tools the maintenance team already uses.

What to be cautious about at this stage?

Firstly, a model that looks perfect in a notebook can stumble the moment it starts reading real-time data. Some factories run on stable, cloud-connected systems but others operate in remote locations where everything has to work locally, right on the machine. In the latter case, you’re building a full end-to-end setup that runs without the internet. It’s much more complex than a cloud deployment, but often the only option.

Not everyone realizes this, but even the interface becomes a decision point – should the dashboard live in a separate app, or right inside the operator’s screen? It always depends on how people work day to day.

And then there are the false alarms. The problem isn’t always in the equipment, as sometimes it’s the sensor itself, worn down by heat, vibration, or time. If a model relies too much on comparing readings between sensors, one bad input can trigger a wave of false positives. That’s why I always recommend validating not only the algorithms but the sensors feeding them, too.

Integration is the final piece. Predictive maintenance data can’t sit in isolation; it has to connect with CMMS or ERP systems so alerts automatically create maintenance tickets or log updates. And technology alone isn’t enough. Every alert needs a clear human response protocol, i.e., who checks it, who acts on it, and how that feedback loops back into the model.

6. Change management & user adoption

Predictive maintenance initiatives can’t come solely from the top. If leadership rolls out a system and expects operators to just “trust the model,” it’s almost guaranteed to fail. The people who know the machines best, like the engineers and technicians using them, need to be part of the building process from day one. Your company needs to start thinking about a change management strategy sooner than later.

When the end users can see why the model predicts an issue and how it connects to what’s happening on the floor, they’re far more likely to use it. One great example can be tools like digital twins, which help visualize this link between data and reality.

And, of course, training and feedback loops are just as important. When the people who use the end solution share their opinions on what works and what doesn’t in the models, it changes the dynamic. Once they see their feedback reflected in updates, they’ll see that the predictive maintenance project is a shared effort.

7. Continuous improvement & scaling

Predictive maintenance challenges don’t end once a model is deployed. The real work begins after the first version goes live. Machines change with time – they settle, wear, and develop quirks that weren’t present in their early life.

A model trained on data from a brand-new machine will not describe a machine that has already run thousands of cycles. I treat this problem the same way I think about running. I cannot expect to run five kilometers today with the same pace I had 10 years ago. The machine can’t either. So I need to decide which period of data represents its current reality and retrain the model around that window. Sometimes that means reducing the amount of data used for training, but the model becomes more truthful because it no longer learns from a past that no longer exists.

When a sensor change breaks the model

Then there are sensor replacements. A measurement point fails. A technician swaps in a new one. The machine looks the same, but the readings shift because the new sensor has slightly different characteristics. The model will drift because it learned from the previous calibration. I’ve handled cases where we recalculated historical data as if the new sensor had always been there. It was like rewinding reality and replaying it through the updated measurement standard. Once we did that, the model stopped wandering and returned to producing stable predictions.

Retraining needs to happen where the work happens

Retraining also depends on where the system lives. A model sitting in a cloud service is one thing. A model installed on a machine that works in remote conditions with no reliable internet is another story. In those cases, everything needs to run locally. The data must flow through hardware that can tolerate dust, vibration, heat, and downtime. Operators should not need to step into a separate tool just to interpret alerts. The predictive system must feel like part of the equipment. That level of integration is rarely simple. It requires understanding how the machine is used, not how it is described in documentation.

Scaling requires proof before expansion

Then comes the temptation to scale. One working model does not automatically mean it should be deployed everywhere. I evaluate whether a new machine or site will benefit in real currency terms. If expanding adds complexity without clear gains, I slow down. Forecasting cost reduction needs cooperation from operations. Without that partnership, scaling becomes decoration rather than improvement.

When digital twin makes sense

Digital twin technology can help here, but only when used with restraint. I like to build a digital twin that represents one meaningful parameter rather than an entire machine. A good example is the exhaust gas temperature between low and high pressure turbines in an aircraft engine. This number reflects the wear on the hot section of the engine. I can measure it directly, yet I also model it based on historical operating conditions. That lets me simulate the future. If the engine continues running the way it has, I can estimate how many more cycles remain before the temperature crosses a threshold. If I adjust certain operating conditions, I can extend its life.

That kind of digital twin is practical. It is small enough to trust, it serves a clear question, and helps plan maintenance in a way that prevents failures and reduces cost. The key is not to build a perfect replica of the machine but a useful one.

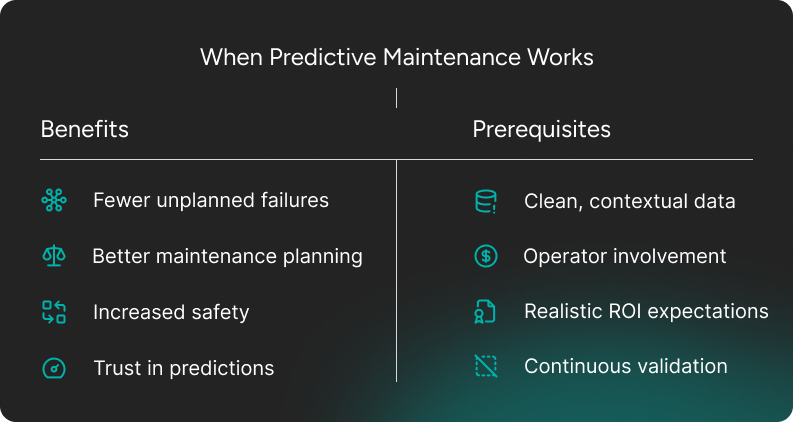

In predictive maintenance, context matters as much as technology

Predictive maintenance can be transformative for companies, but only when each stage of the implementation is handled with care. What I’d like to stress here is that the biggest challenges don’t relate purely to technological choices, but also to context. It’s about knowing which data matters, ensuring your models understand the real-world environment, and getting people on the ground to trust and use the results.

Building a reliable PdM system takes collaboration between engineers, data teams, and operators, plus a willingness to refine both technology and process as new insights emerge.

Thinking about starting a predictive analytics project but not sure where to begin? Our team can help you shape it from both the data engineering and AI angles – from setting up the right data foundations to designing models that make a difference on the floor. Take a look at our data engineering services to see how we can help.