Rethinking data governance: From IT task to organizational discipline

Many companies see data governance primarily as a technical task, something for IT to handle. In reality, it is first and foremost an organizational and managerial challenge.

Yes, IT will build the pipelines and run the tools. But success depends on aligning teams, roles, and responsibilities so data can be used. I write this as a data engineer who’s seen both failure and success when governance was done right.

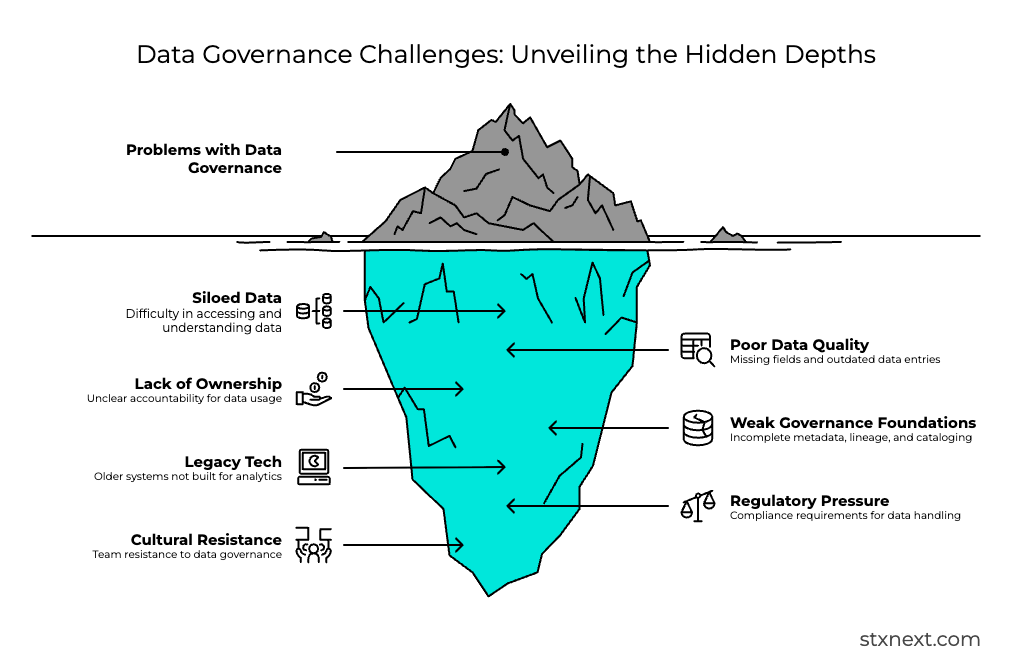

In this article, I discuss the most common challenges at different stages, along with what you can do about them. Some stem from the current state of data silos, unclear ownership, and poor metadata. Others appear when companies attempt to implement or scale governance across the organization.

Current-state challenges – before data governance implementation

Making sense of siloed data

While it might seem surprising (or even controversial to some), I don’t treat “siloed data” as a problem in and of itself.

The real issue appears when a company cannot explain what sits inside those silos. According to Atlan, knowledge workers lose about 30% of their workweek searching for information instead of using it.

From my experience, data teams see an even sharper gap, spending the majority of their time just attempting to find where each data lies.

As a rule of thumb, the larger the company, the bigger this issue becomes. People assume they know their own environment, but when they begin their data governance efforts they often realize there are systems that nobody remembers owning. The fact that these systems are still in operation often comes down to sheer luck, i.e., they simply haven’t broken down yet.

Having a centralizedsingle source of truth as a solution might be beneficial, but it does not always match the way organizations operate. Companies run many systems, and each came to life at a different time, carrying its own history and structure. The goal for business should be, first and foremost, knowing what lives inside them.

Poor data quality & lack of observability

Many companies gather vast amounts of data. As mentioned, the more data, the more likely it is to spot missing fields and outdated entries. Or places where free-text values are used instead of a standardized structure, which would have been beneficial from the start. These issues often grow because the organization lacks enough data-literate people to maintain governance, SLAs, and documentation.

At this point, however, I’d like to underline that data quality is not a core goal for data engineers on a governance project. However, since governance brings order to how data is defined and handled, data quality improves as a side effect. Not because we chase every imperfect record, but because the organization finally stops producing mismatched answers to the same question.

When technical teams are part of the governance project, they put structure around the silos so teams stop shaping the same data in different ways (which is where most of the trouble begins).

This is also where creating clear data policies becomes important. Policies that establish required fields (so there are no missing fields), consistent naming conventions, and shared standards for how information should be entered.

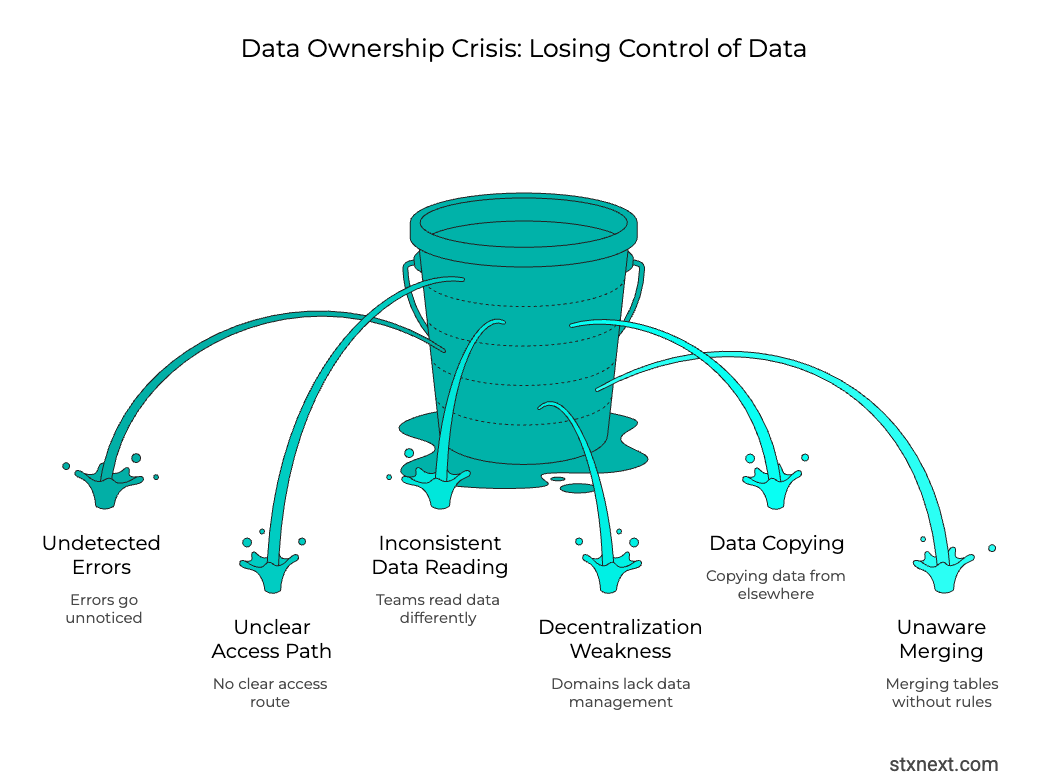

No clear data ownership or accountability

When no one owns a dataset the organization begins to lose control of how that data is used. The course of action usually looks like this:

Errors are undetected → access questions have no clear path → teams start reading the same fields in different ways.

As my colleague Krzysztof Sazon noted in his article "Is Your Company Ready for Data Mesh?", decentralization works only when every domain has the strength to manage its own data, and many teams do not. They copy data from elsewhere to compensate and might merge their own tables without knowing the rules that shaped the original.

This issue would be avoided with a data governance committee, who’d make sure each discipline within the business has an owner.

Weak governance foundations

Many problems that appear later in analytics work come from the basics not being in place. There are three subsets of challenges – those around metadata, lineage, and cataloging.

When metadata is incomplete people guess what a field means or how it should be used. Each team fills those gaps differently.

Lineage gaps have the same effect, because people can’t retrace where a piece of data originated from.

As for cataloging, instead of using clear, updated descriptions of datasets, organizations often rely on scattered sheets or outdated wikis. This is where governance can offer one of the most immediate benefits.

The key is not to build one place for everything but to give teams a reliable starting point when they look for data.

Legacy tech and architecture not built for analytics and AI

Older systems often sit at the center of daily operations, but many were never designed for advanced analytics or data science work. They store data in rigid formats, provide little metadata, and offer limited integration options. Engineering teams must build workarounds to extract information, but these scripts break easily and provide no lineage.

This is not something a data governance initiative is meant to fix. Governance does not replace technologies or force teams to switch their tooling. After governance is in place, the same teams continue using the systems they had. The difference is that their work becomes visible, because each team appears in the catalog with its data products, ownership, quality rules, and naming standards. So, the difference is around accountability.

Regulatory pressure

This is where we can understand why, as mentioned at the beginning of this post, data governance is primarily a managerial and organizational project.

In industries bound by laws such as GDPR or HIPAA the company must always know what data it holds, where it lives, and how it has been used.

For example, let’s take the basic right people have according to GDPR, i.e., the right to be forgotten.

A request to delete personal data is simple only when you can locate every place where that data appears. In large organizations with many warehouses this is nearly impossible without governance.

When data is cataloged and described they can point to where sensitive information sits and what rules apply to it. Large organizations need a Data Compliance Officer who understands the legal side, defines what counts as confidential in that particular use case, and ensures the rules are followed. IT, in turn, knows where the data is stored and can act on those rules. This shows the overlap between those two disciplines very well.

Cultural and organizational resistance

Lastly, I’d like to underline that governance depends on people, not just on the technology behind it.

The social side decides whether the project succeeds, because if there’s team resistance then the governance model will collapse. You can do everything I’ve already mentioned – build the catalog, define the roles, automate workflows, set up compliance functions, and form committees. Teams may decide they do not have time to align, they see no benefit, or they simply prefer their current habits.

Employee morale might also drop, since they might not understand why their role is being so strongly affected or transformed (seemingly overnight).

How much resistance you face depends on your company’s approach. Some organizations mandate governance and compliance, but others only “invite” team members to follow the new rules.

From my experience, the success of a data governance implementation also depends on how much of the company it covers, because the program doesn’t need to apply to the entire organization. One domain can adopt it first, which is likely to boost the chances of success. But even then, leaders must decide whether they truly want to push the change, or they themselves aren’t convinced (because leadership sees it as an unnecessary burden).

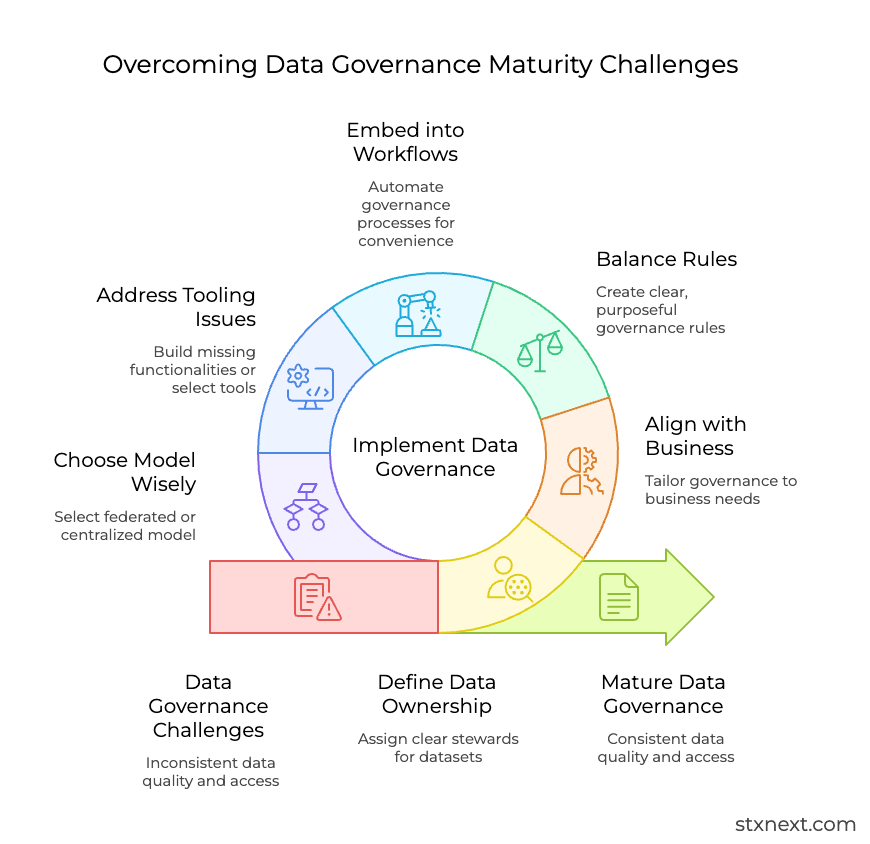

Data governance implementation & maturity challenges

Now, let’s assume that a company has already decided to implement governance. Here are the main challenges they are likely to face, and my suggestions on how to approach them.

Defining data ownership

Multiple departments may believe they influence a dataset, but no one feels fully accountable for its quality, access decisions, or documentation. This can create delays, and trigger constant debate about who should maintain or approve what.

How to approach it:

Let’s go back to the core principle of data governance – treat data as a product. And every product must have an owner. When you define a dataset as a data product, place it in the catalog with a clear steward.

That person or team will own its quality, access rules, and updates. They’ll shape how the product evolves and explain how others should use it.

The difference here is moving to explicit responsibility.

Aligning governance with business use cases

A single rulebook cannot cover every context. Finance, healthcare, retail, and manufacturing all work with distinct types of information. They face different risks, and operate under their own regulatory frameworks.

How to approach it:

You need a governance structure that reflects the business rather than a generic template. Set up a committee who’ll create high-level rules. It should define what the organization expects from its data products, how to handle sensitive information, and which regulations apply.

Then there’s work within individual domains. Owners need to receive these rules and adapt them to their systems. They decide what fits their workflow and what requires additional safeguards. Naturally, all within the industry and individual business context.

Over-engineering or under-engineering the rules

This challenge can result from implementing too many policies and levels of bureaucracy, or rules that are too vague and have no impact.

How to approach it:

This point ties directly back to the committee’s work. Each rule they create needs a clear purpose and a clear owner. Teams should know what it means for their systems and how to put it into practice.

I believe that businesses need to realize governance collapses when the rulebook grows faster than the organization can digest it. So, maintaining balance (or, as I suggested earlier, applying governance area by area instead of company-wide) might be the best choice.

Embedding governance into workflows

Governance fails when it exists only on paper. If teams need to remember rules manually or jump between tools to follow them, adoption breaks down.

How to approach it:

A workable governance setup will be best if it’s based on automation.

A catalog should let people search and filter data without digging through spreadsheets. Access should not depend on sending emails to a person who’s responsible for access management and hoping someone replies.

From my experience on projects, you need to make it as convenient and fast to request and grant access as possible. I worked on a platform, which featured a simple button for access requests. Once clicked, a notification went to the right owner. To approve or reject it, the person also only needed to click on a relevant button.

The identity and access management workflow behind it handles the rest. Of course, automation doesn’t remove every manual decision, but it does remove friction.

Challenges with tooling

Tooling introduces two kinds of problems – technical and cultural.

As of the time of writing, there wasn’t a single platform that would cover the full scope of governance. Even the major cloud tools like DataZone, GCP Dataplex, and Azure Purview solve only part of the goals. This is especially visible in multi-cloud setups. One tool may catalogue assets well but another tool might not.

Even once you sort out the issues with tooling, there’s the case of encouraging people to follow new compliance rules.

How to approach it:

When these problems happen the company must build missing functionalities, workflows, or full-scale tools internally. It’s a much broader task than building connectors, it usually becomes a sizable project rather than a quick patch.

In any case, the task is to assemble a toolset that reflects the company’s environment. Then you fill the gaps with internal development or with the help of a data governance consultancy. A partner can help assess needs and select the right combination, but there is no way to avoid some manual work.

As for potential adoption issues, make training part of the rollout, and not something that will be planned for “later”. And expect resistance, because governance always requires people to shift how they work. The tools will only succeed when teams adopt them, not when the organization launches them.

Federated vs centralized models

As a governance program grows, you eventually face the question of who should make the decisions. A centralized model gives you consistency, but can feel detached from what individual domains need. A federated model moves decisions closer to the teams, but risks uneven practices.

How to approach it:

There is no universal answer. Some companies benefit from a local, domain-focused setup because it touches a smaller part of the organization and is easier to adopt. Others need a broader structure to keep scattered teams aligned. So, if I were to name one factor to prioritize, it would be scale. A small or mid-size firm does not need a system built for enterprise complexity, but a large company cannot function without it.

Also, remember to look beyond the current state of the organization – maybe there are some expansion plans, mergers, or any other factors that could change the structure in the foreseeable future?

Data governance is a continuous journey

Good data governance gives a company room to work with its data instead of fighting it. When ownership is clear and the basic structure makes sense, teams stop guessing and start building.

The goal is creating an environment where people can rely on the information in front of them and move faster with less stress. With that foundation, the organization can grow its data ambitions without losing control.

If you’re unsure how to proceed with your data governance strategy, explore our data governance consulting services – we’ll be happy to advise you on the best direction, given your company specificity and the technology you currently rely on.